The badaud is predominantly male, but women are allowed to stop and stare and mingle and gossip as well. The badaud, by contrast, is always liable to form a group or crowd, either for a mass gawk or some communal response. The flaneur is of a higher social class, a borderline artist, and a loner: you cannot imagine a concatenation of flaneurs eagerly exchanging observations. If the flaneur is an active idler, the badaud is a stationary, passive one, ready to stare open-mouthed at any phenomenon that offers novelty or puzzlement.

This was the badaud, or gawker: one who stands and stares at anything going on-a carriage accident, a fire brigade in a hurry, a sudden police arrest, or a suicide being fished from the river. The flaneur has also had an echoing afterlife: my first novel ( Metroland, 1980) featured two pretentious adolescents in the London of 1963 who theorize that by “lounging about in a suitably insouciant fashion, but keeping an eye open all the time, you could really catch life on the hip-you could harvest all the aperçus of the flâneur.” Their anachronistic questing is only partially successful.īut there was another character on the Paris street at that time, who had already been there for centuries but was less noticeable and less fashionable. It’s tempting to imagine tourists in the first half of the Belle Epoque waiting on boulevards to see one pass by with cane, monocle, and superior expression. Identified by Baudelaire in his essay “The Painter of Modern Life” (1863), he has become as essential to our picture of that period as the demimondaine, the fashionable café dansant, the top hat, and the glass of absinthe. A psychogeographer perhaps, avant la lettre. The flaneur was a familiar figure in nineteenth-century Paris: a solitary, quasi-artistic man (though not always) who strolled the streets like an urban epicure.

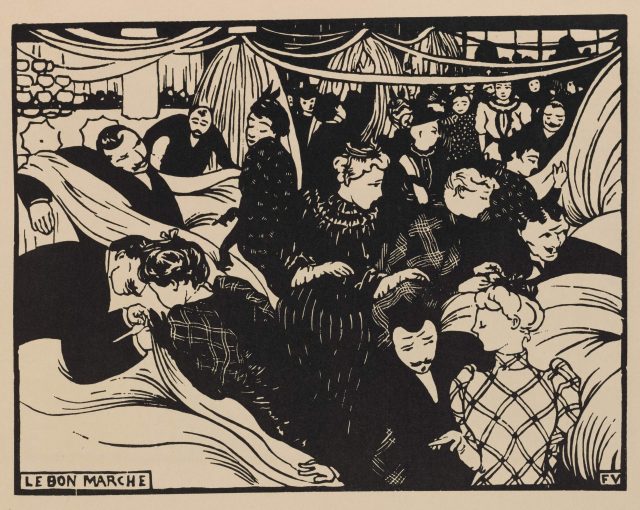

Private Collection/Fondation Félix Vallotton, Lausanneįélix Vallotton: La Loge de théâtre, le monsieur et la dame, 1909

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)